Semiconductor Industry Trends Report 2026

The global semiconductor industry enters 2026 at a decisive inflection point.

Executive summary

What was once a cyclical market led mainly by consumer electronics has become a structurally strategic industry supporting artificial intelligence, electrification, connectivity, healthcare, defence and industrial productivity. Semiconductors are no longer viewed simply as components used deep within products. They are now recognised as foundational infrastructure, that can be compared in importance to energy networks and digital communications.

By 2026, global semiconductor revenues are firmly back on a long‑term growth trajectory following the volatility of the early 2020s. Demand growth is broader and more resilient than in previous cycles, with multiple end markets expanding in parallel rather than sequentially. Data centres, automotive electrification, industrial automation and AI‑enabled devices are all contributing meaningfully to growth.

This diversification reduces dependence on any single market, but it also introduces new operational challenges around forecasting, lifecycle planning and inventory management.

On the supply side, the industry is undergoing a structural transformation. Capital intensity has reached unimagined levels, manufacturing capacity is increasingly regionalised, and geopolitical considerations now influence sourcing decisions alongside cost and performance. At the same time, sustainability pressures and export controls are reshaping how chips are designed, manufactured and distributed.

This report examines the defining semiconductor trends shaping 2026, drawing on PwC’s Semiconductor and Beyond outlook alongside wider industry analysis. It interprets these trends through a practical lens relevant to semiconductor manufacturers, OEMs, EMS providers and supply chain leaders. While the perspective is deliberately neutral and analytical, it reflects a clear industry reality: organisations that actively manage component lifecycles, excess inventory and supply chain resilience will be better positioned to protect margins and capture value as complexity increases.

Key statistics at a glance

- The global semiconductor market is projected to exceed $1 trillion in annual revenues before 2030, with strong momentum already evident by 2026

- Data centre and server-related semiconductors are forecast to grow at double‑digit annual rates, driven primarily by AI workloads

- Automotive semiconductor demand is expected to grow at over 10% CAGR, significantly outpacing global vehicle production

- Compound semiconductors, particularly silicon carbide, are projected to account for more than 50% of automotive power semiconductor value by 2030

- Advanced packaging adoption is accelerating as transistor scaling slows, becoming a primary driver of performance improvement

- Global data centre electricity consumption is expected to more than double by 2030, increasing the strategic importance of energy‑efficient semiconductor design

How to read this report

- Time horizon: Focus on 2026, with implications through to 2030

- Geography: Global, with emphasis on the US, Europe and Asia‑Pacific

- Perspective: Demand, supply, technology, regulation and lifecycle risk

- Audience: Semiconductor manufacturers, OEMs, EMS providers, procurement leaders and policymakers

1. Semiconductor demand in 2026: growth drivers and end markets

Semiconductor demand in 2026 reflects a fundamental shift away from single‑market dependency towards a multi‑pillar growth model. Historically, the industry moved through relatively predictable cycles, driven first by PCs, then smartphones, and later by cloud computing. In contrast, the mid‑2020s are defined by several overlapping demand engines advancing simultaneously.

This diversification is strategically positive, reducing the risk that weakness in one segment triggers a global downturn. However, it also complicates forecasting and capacity planning. Different end markets operate on different demand cycles, qualification timelines and pricing structures, increasing the likelihood of mismatches between supply and demand.

1.1 AI and data centres as the primary growth engine

The rapid adoption of generative AI since 2022 has permanently altered global compute requirements. By 2026, AI workloads account for a substantial share of new data centre investment, reshaping both the scale and composition of semiconductor demand.

Modern data centres are increasingly optimised for AI rather than general‑purpose computing. This drives demand for high‑performance CPUs and GPUs, custom AI accelerators, high‑bandwidth memory and sophisticated networking and power management chips. Semiconductor value per server continues to rise sharply, even where unit growth moderates.

A notable development is the rise of custom silicon. Major cloud service providers are designing application‑specific accelerators tailored to internal workloads. While this reduces reliance on off‑the‑shelf processors, it increases overall chip complexity and places additional pressure on advanced manufacturing and packaging capacity.

From a supply chain perspective, AI‑driven demand introduces concentration risk. Advanced logic, memory and packaging capacity are tightly constrained, and lead times remain long. Forecasting errors can quickly result in either shortages or excess stock, making lifecycle planning and secondary market strategies increasingly important.

1.2 Automotive electrification and software‑defined vehicles

Automotive electronics currently represent one of the most structurally attractive semiconductor markets. Electrification, advanced driver assistance systems, and the shift towards software‑defined vehicles are increasing semiconductor content per vehicle at a pace far exceeding growth in vehicle production.

Electric vehicles require substantially more power semiconductors than internal combustion engine vehicles. High‑voltage inverters, onboard chargers and battery management systems increasingly rely on silicon carbide and gallium nitride devices to improve efficiency, reduce thermal losses and extend driving range.

At the same time, assisted and autonomous driving functions are driving demand for cameras, radar and LiDAR sensors, high‑performance system‑on‑chip devices and secure connectivity microcontrollers. The architectural shift from distributed electronic control units to zonal and centralised computing further concentrates semiconductor value into fewer, more critical components.

This concentration increases exposure to lifecycle risk. Automotive qualification cycles are long, redesigns are costly and unexpected end‑of‑life events can disrupt production for years. As a result, proactive component lifecycle and inventory management is becoming a strategic capability rather than an operational afterthought.

1.3 Consumer devices and on‑device AI

The smartphone and PC markets may be mature in terms of unit sales, but 2026 marks a clear shift toward value driven by on-device AI. Neural processing units are now integrated directly into system-on-chip designs, allowing devices to run AI features in real time without relying on the cloud. This improves latency, privacy, and overall reliability.

This shift increases demand for advanced logic nodes, low‑power memory and tighter system integration. While shipment volumes are relatively stable, semiconductor content per device continues to rise, particularly in premium segments.

However, rapid product refresh cycles increase the risk of obsolescence. As AI capabilities evolve quickly, devices can become outdated sooner than expected, raising the likelihood of excess or mismatched inventory if demand forecasts are inaccurate.

See how we help you recover value from your excess

1.4 Industrial, energy and healthcare applications

Industrial automation, renewable energy and digital healthcare continue to adopt semiconductors at a steady pace. Although growth rates are lower than in AI or automotive, these markets offer longer product lifecycles, higher reliability requirements and greater demand predictability.

Power semiconductors are critical to renewable energy generation and grid infrastructure, while sensors, connectivity ICs and embedded processors underpin smart manufacturing and medical diagnostics. Supply disruptions in these sectors can have disproportionate downstream effects, reinforcing the importance of resilient sourcing strategies.

2. Supply dynamics in 2026: capacity, geography and resilience

While demand sets the market direction, supply constraints determine the pace at which the semiconductor industry can respond. Currently, supply dynamics are shaped not only by market economics but also by geopolitics, regulation, capital availability, and long-term risk management decisions. The defining characteristic of the current cycle is reduced flexibility. Capacity decisions made years earlier now constrain present-day outcomes, increasing the persistence of both shortages and surpluses.

2.1 Mature-node shortages versus leading-edge oversupply

One of the most misunderstood features of the current semiconductor landscape is the coexistence of leading-edge investment and mature-node scarcity. While headlines often focus on advanced nodes below five nanometres, many of the most acute shortages in recent years have occurred at mature nodes used for automotive, industrial and power applications.

These nodes are less attractive for capital investment. Margins are lower, scaling benefits are limited, and customers demand long product lifecycles rather than rapid technology refreshes. As a result, capacity expansion has lagged demand growth. In contrast, leading-edge capacity has seen heavy investment driven by AI and high-performance computing, creating the potential for oversupply if AI demand softens or shifts more quickly than expected.

This imbalance creates structural risk. Mature-node shortages can halt production lines even when advanced capacity sits underutilised. From a supply chain perspective, this reinforces the importance of component-level visibility and proactive lifecycle management.

2.2 Why automotive and industrial chips remain structurally vulnerable

Automotive and industrial semiconductor demand differs fundamentally from consumer electronics. Qualification cycles are long, redesigns are costly and components are often expected to remain available for a decade or more. These characteristics limit flexibility when supply disruptions occur.

Automotive programmes are particularly exposed to end-of-life risk. A single discontinued microcontroller or power device can delay production or force expensive redesigns. Industrial systems face similar challenges, especially where certification or safety compliance is required. These vulnerabilities persist in 2026 despite increased awareness because underlying structural constraints remain unresolved.

2.3 Inventory distortion from double-ordering and cancellations

Periods of scarcity often trigger defensive behaviours, including double-ordering and inflated forecasts. While rational at an individual company level, these practices distort demand signals across the ecosystem. When conditions normalise, cancellations cascade through the supply chain, leaving excess inventory concentrated in specific components or regions.

This phenomenon has contributed to recent boom-bust dynamics, particularly in memory, analogue and certain logic categories. The result is not a simple surplus, but a mismatch between what is available and what is required. Managing this distortion increasingly requires secondary market mechanisms rather than traditional procurement responses.

2.4 How secondary markets absorb structural imbalances

Secondary markets play an increasingly important role in rebalancing the semiconductor ecosystem. By enabling the redeployment of excess stock to alternative users, OEMs and EMS companies release trapped working capital and reduce waste. In 2026, these markets are no longer purely transactional; they provide intelligence on lifecycle status, pricing signals and emerging constraints.

For OEMs and EMS providers, engaging proactively with secondary markets supports resilience without compromising quality or compliance when managed correctly.

3. Technology trends defining semiconductor innovation in 2026

Technological progress in the semiconductor industry has entered a more complex phase. For decades, performance improvements were driven primarily by transistor scaling. By 2026, innovation is multidimensional, spanning architecture, materials, packaging and system-level optimisation.

3.1 Chiplet economics versus monolithic designs

Chiplet architectures represent a fundamental shift in semiconductor economics. Rather than manufacturing a single large die (a small, rectangular or square piece of semiconductor material, such as silicon, that forms the foundation of integrated circuits), designers combine multiple smaller dies, potentially fabricated on different process nodes. This approach improves yields, reduces cost and increases design flexibility.

However, chiplets also introduce complexity. Interconnect standards, packaging yield and test requirements become critical cost drivers. While economically attractive at scale, chiplet-based designs demand mature ecosystems and tight coordination across the supply chain.

3.2 HBM and memory bottlenecks in AI systems

High-bandwidth memory has become a critical bottleneck in AI systems. Performance gains from advanced processors are increasingly constrained by memory bandwidth and availability. HBM production is capital-intensive and highly concentrated, increasing systemic risk.

In 2026, memory availability influences not only system performance, but delivery schedules and pricing. This elevates memory from a supporting component to a strategic constraint requiring dedicated planning.

3.3 Why advanced packaging shifts risk downstream

As advanced packaging adoption accelerates, risk migrates downstream to assembly, test and packaging providers. Yield losses, longer qualification timelines and capacity constraints can delay product launches even when front-end fabrication is available.

This shift requires closer integration between design, manufacturing and supply chain teams. Packaging is no longer a back-end afterthought, but a determinant of commercial success.

3.4 Technology adoption timelines versus procurement realities

Technology readiness does not always align with procurement capability. New process nodes or materials may be technically viable but lack sufficient supply maturity for volume deployment. This mismatch can create hidden risk when components are designed in prematurely.

Organisations that align design roadmaps with realistic sourcing timelines reduce exposure to late-stage disruptions and excess inventory.

4. Sustainability, regulation and lifecycle risk

In 2026, sustainability and regulation are no longer peripheral considerations in the semiconductor industry. They now sit alongside cost, performance and availability as core decision variables. According to PwC, environmental performance, regulatory exposure and supply chain transparency are increasingly influencing both customer selection and investor confidence across the semiconductor value chain.

4.1 Carbon cost of fabs versus product lifecycle emissions

Semiconductor manufacturing is one of the most energy-intensive industrial processes in the global economy. According to PwC, the majority of a semiconductor’s carbon footprint is generated during fabrication rather than during its operational lifetime. Leading-edge fabs require continuous, high-load electricity consumption to maintain ultra-clean environments, advanced lithography systems and thermal stability.

This creates a structural imbalance in emissions accounting. While downstream customers often focus on product-level efficiency gains, the upstream carbon cost of manufacturing dominates total lifecycle emissions. According to the International Energy Agency, electricity demand from data centres and semiconductor manufacturing combined is expected to grow rapidly through the late 2020s, increasing pressure on manufacturers to decarbonise energy sourcing rather than relying solely on efficiency improvements.

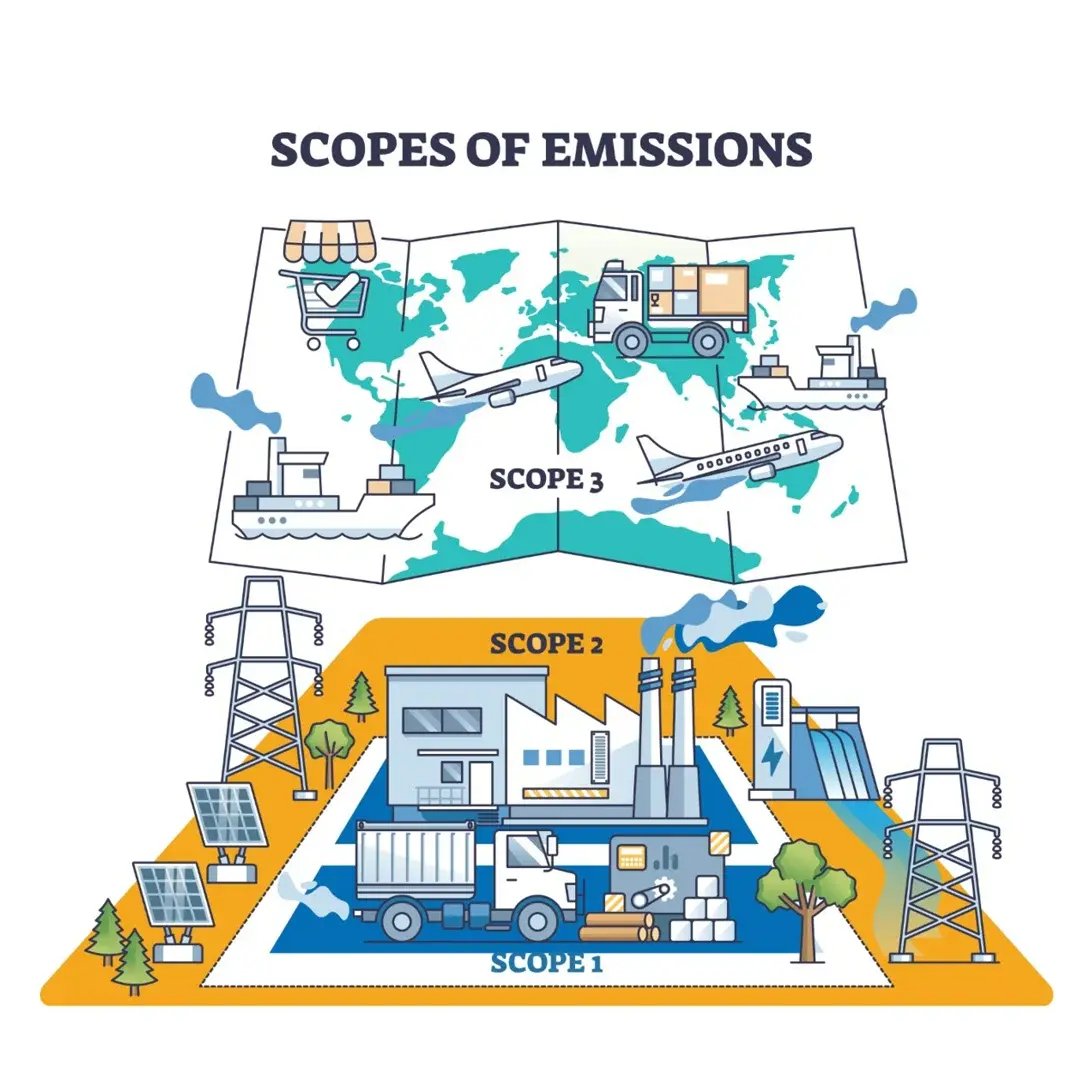

For OEMs and EMS providers, this dynamic matters because supplier emissions increasingly flow into scope three reporting. Semiconductor sourcing decisions therefore carry reputational and regulatory implications beyond cost and performance.

4.2 Water usage constraints and regional exposure

Water availability has emerged as a material operational risk for semiconductor manufacturing. SEMI data indicates that advanced fabs can consume millions of litres of ultra-pure water per day. Many major fabrication hubs are located in regions experiencing increasing water stress, including parts of East Asia and the southwestern United States.

Interruptions to water supply can halt production entirely, creating a risk profile comparable to energy shortages. As a result, water recycling capabilities and regional water resilience are becoming differentiators between fabrication sites. From a supply chain perspective, geographic concentration amplifies exposure, particularly for mature-node capacity serving automotive and industrial markets.

4.3 Regulation as a driver of forced obsolescence

Export controls, environmental regulations and safety standards increasingly shape semiconductor availability. According to Gartner, regulatory interventions can accelerate component end-of-life timelines by restricting where and how products can be sold or manufactured.

These changes introduce forced obsolescence that is not driven by technology progression, but by compliance requirements. Components that remain technically viable may become commercially unusable, creating sudden inventory write-down risk for OEMs and EMS providers.

4.4 Financial impact of compliance-driven redesigns

Compliance-driven redesigns impose both direct and indirect costs. Direct costs include engineering effort, requalification testing and certification. Indirect costs include delayed product launches, lost revenue and stranded inventory. McKinsey estimates that redesign cycles triggered by regulatory change can add months to development timelines and materially increase programme costs.

Organisations that integrate regulatory intelligence into lifecycle planning are better positioned to anticipate these disruptions and reduce financial exposure.

5. Inventory, obsolescence and capital efficiency

Volatility, long lead times and fragmented supply chains have transformed inventory from an operational necessity into a strategic asset class. In 2026, inventory decisions directly affect cash flow, resilience and competitive positioning across the semiconductor ecosystem.

5.1 Why volatility creates both shortages and excess

Semiconductor supply chains operate on long planning horizons, often exceeding 12 to 24 months from capacity decision to output. When demand accelerates unexpectedly, supply cannot respond quickly, resulting in shortages. Conversely, when demand softens or shifts between segments, previously committed capacity continues to deliver, creating surplus.

Gartner notes that this structural lag effect is a primary driver of the industry’s boom-bust cycles. The coexistence of shortages and excess is therefore not an anomaly, but a predictable outcome of long lead times and imperfect forecasting.

5.2 Balance-sheet impact of excess and obsolete stock

Excess and obsolete inventory ties up working capital and exposes organisations to rapid value erosion. PwC highlights that inventory write-downs directly reduce operating margins, while indirect costs include storage, insurance and reduced organisational flexibility and efficiency.

For EMS providers and OEMs operating at scale, even small percentage write-downs can translate into millions of pounds in lost value. As interest rates remain elevated relative to the previous decade, the opportunity cost of trapped capital has increased materially.

5.3 Inventory as a strategic asset class

Increasingly, leading organisations manage inventory as a portfolio rather than a static buffer. Segmentation by lifecycle stage, demand criticality and redeployment potential enables more informed decision-making. According to industry best practice benchmarks cited by PwC, companies with high inventory visibility are better able to absorb shocks without over-ordering.

This strategic framing recognises that not all inventory carries equal risk. Components nearing end-of-life require different treatment from those supporting long-term programmes.

5.4 Redeployment and resale to improve capital efficiency

Redeploying surplus components internally or reselling them through controlled secondary channels can recover significant value. Industry data shows that structured resale programmes reduce waste while improving capital efficiency.

When managed transparently and compliantly, secondary market engagement supports resilience without undermining quality or traceability. This capability is increasingly viewed as a core component of mature supply chain strategy rather than an emergency measure.

Strategic implications for industry stakeholders

OEMs and EMS providers

- Balance leading‑edge investment with resilient mature‑node capacity

- Strengthen partnerships across design, packaging and equipment ecosystems

- Embed sustainability and compliance into capital planning

- Diversify sourcing and avoid single‑point dependencies

- Improve forecasting, lifecycle planning and inventory intelligence

- Treat excess stock management as a strategic capability

Scenario-based outlook: 2026–2028

Looking beyond 2026, the semiconductor industry faces multiple plausible trajectories. Scenario-based planning provides a more robust framework than single-point forecasts, particularly in an environment characterised by geopolitical uncertainty and rapid technological change.

Base case: sustained but uneven growth

In the base case, global semiconductor demand continues to grow at a healthy pace through 2028, driven by AI infrastructure, automotive electrification and industrial automation. According to PwC and Gartner consensus forecasts, growth remains positive but uneven, with periodic imbalances between segments.

Supply expands gradually as new capacity comes online, but long lead times prevent rapid rebalancing. Inventory discipline and secondary market mechanisms play an important role in smoothing volatility.

Upside case: accelerated AI adoption and electrification

In the upside scenario, AI adoption accelerates faster than anticipated, and electrification timelines compress. Demand for advanced logic, memory and power semiconductors exceeds current projections. SEMI capacity data suggests that under this scenario, utilisation rates remain high and pricing power strengthens.

The risk in this case lies in overextension. Aggressive capacity commitments could create future oversupply if growth moderates.

Risk case: geopolitical escalation or AI investment slowdown

In the risk scenario, geopolitical escalation disrupts trade flows or regulatory intervention slows AI investment. Advanced-node capacity faces underutilisation, while mature-node vulnerabilities persist due to structural underinvestment.

Under these conditions, excess inventory accumulates rapidly, particularly in components tied to paused programmes. Organisations with flexible sourcing strategies and active inventory redeployment capabilities are better positioned to protect margins.

Component Sense’s excess stock solutions are designed to address this challenge before value is lost. Through solutions like InPlant™, Consignment and Outright Purchase, we help manufacturers regain control of surplus inventory, freeing up cash, reducing storage and obsolescence risk.

This, in turn, keeps viable components in productive use rather than being written off or scrapped. The result is a more resilient, commercially efficient approach to inventory management that turns volatility into an opportunity rather than a liability.

Implications for sourcing and inventory strategies

Across all scenarios, flexibility emerges as the defining competitive advantage. Companies that invest in lifecycle intelligence, diversified sourcing and proactive inventory management are better equipped to adapt to divergence rather than convergence.